As James Pembroke and I say in Dataproof Your School (2022, p4), the extensive body of research into teaching, learning and schooling suggests that students need to be in school, in class, focused and learning what we want them to.

Here, we will focus on the first two areas: are students in school and in class?

What do we know about the trends over time? What do we know about the current situation? What are the best bets to ensure that students are in school and in class? What should schools do to address missed learning?

It is important to note that students’ attendance is recorded twice each school day (morning and afternoon) and that these are referred to as ‘sessions’ of attendance. So with 190 school days per year, there are 380 potential sessions a student should attend.

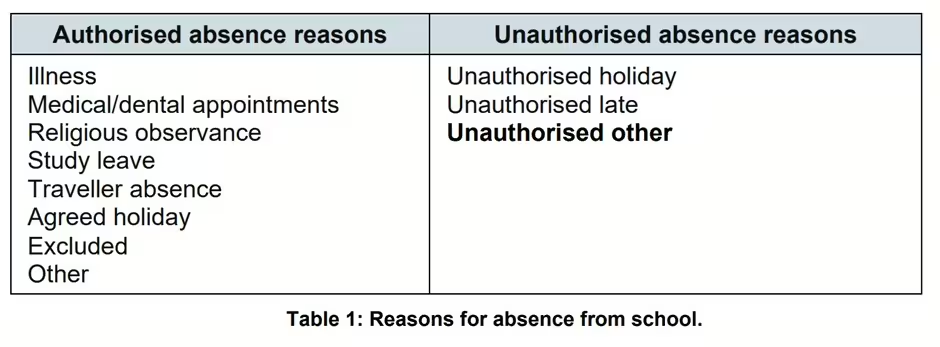

In England, the Department for Education and its predecessors have been collating data on pupil attendance and reasons for absence since the early 2000s. Student absence is grouped into authorised and unauthorised absence.

Whilst some details have changed since the Covid shock of 2020, we know the following.

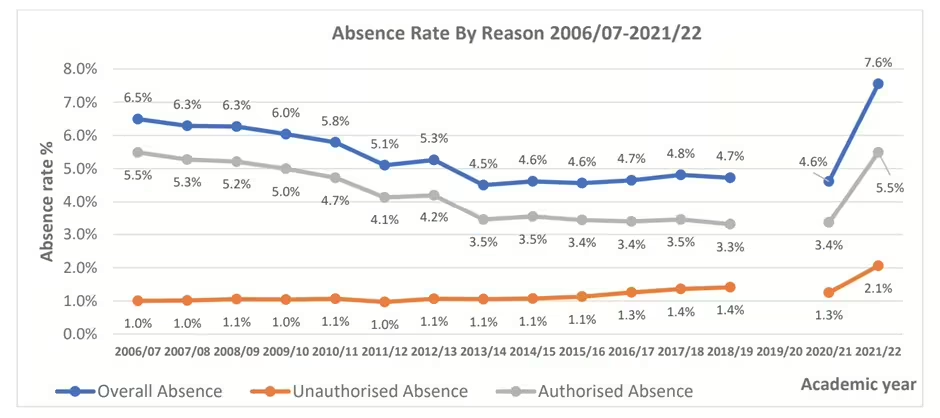

Overall absence dropped from 6.5% in 2006/7 to around 4.6% in 2013-19. It rose to 7.6% in 2021/22.

Pre-pandemic, authorised absence had stabilised at around 3.8%; this category of absence is mostly due to student illness (around 3%). Authorised absence was decreasing over time, from 5.5% in 2006/7 to 3.3% in 2018/19, whichis likely to have been due to schools increased focus on maximising school attendance.

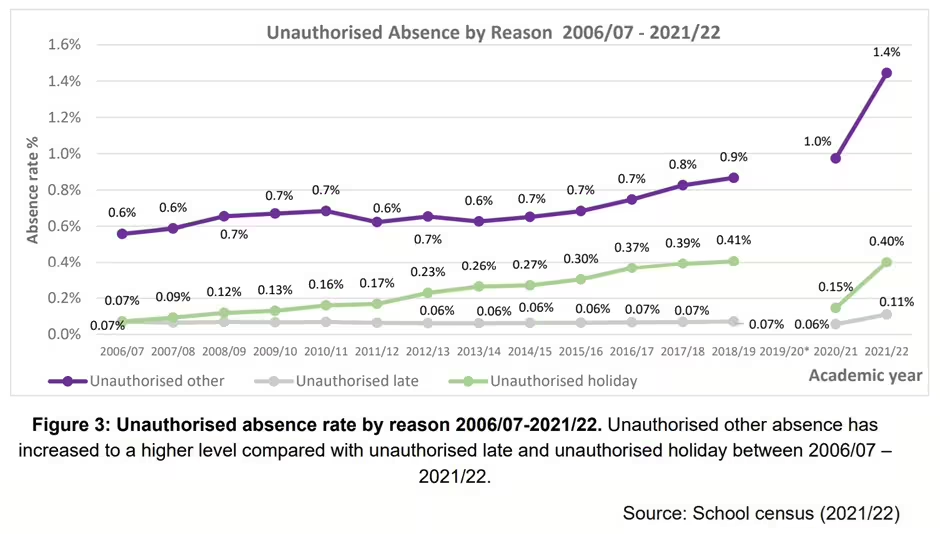

Unauthorised absence was increasing over time as schools were encouraged to disallow absence and decreased the likelihood that they would authorise non-attendance at school. As per the table above, unauthorised absence is defined as students being late and arriving after registers have closed (code U), being absent due to family holiday (G) or absent for any other reason (O, often referred to as Absent Unauthorised Other, or AUO) not covered by the first two categories of unauthorised absence. Unauthorised absence is mostly due to AUO.

Pre-pandemic, late arrivals to class accounted consistently for less than 0.1% of all unauthorised absences, rising slightly to 0.11% in 2022/23.

As authorised absences decreased into the 2010s, unauthorised absence rose as previously shown. The increase in unauthorised absence is largely due to more absence being marked Absent Unauthorised Other, with some increase due to schools being required to refuse to authorise family holidays in term time.

It is clear from these data that most students are in school most of the time: over 50% of students have less than 5% absence.

Some students are absent more than 10% of the time. This group is labelled Persistently Absent. This had settled at around 10% of pupils in 2015-19 but has risen to around 20% (the level in 2006/9) since the pandemic, mostly driven by more secondary pupils being flagged as persistently absent. Illness is a major component of persistent absence with 7.8% of all pupils missing 10% or more sessions due to illness alone.

Some students are absent more than 50% of the time. This group is labelled Severely Absent. 2.0% of pupil enrolments were severely absent in Autumn 2023/24

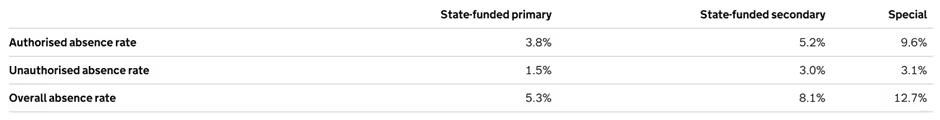

Absence looks different in Primary Schools and Secondary Schools, and both are different to Special Schools.

Data for Autumn 2023/24

The government has introduced various measures to tackle absence. Families can face penalties for keeping children away from school; a fine of £60 per child (due to rise to £80 per child from August 2024, potentially rising to £160 per child for further long absences within three years) can be approved by school and issued by a local authority for a period of unauthorised absence. Local authorities can also seek Education Supervision Orders or prosecutions if they deem fit.

Prior to August 2024, local authorities varied in their approach to issuing fines (see for example these two different approaches: Middlesborough and Dorset).

From August 2024, schools are required to consider triggering fines if a pupil misses 10 or more sessions within any 10-week period, with a new National framework for penalty notices which includes the following:

Analysis suggest that prior to August 2024, this would have meant that ‘around 1 in every 5 pupils is at risk of falling below the proposed new absence threshold. This risk is higher for pupils in secondary schools than those in primary. Disadvantaged pupils and those with special educational needs are at greater risk than other pupils.’

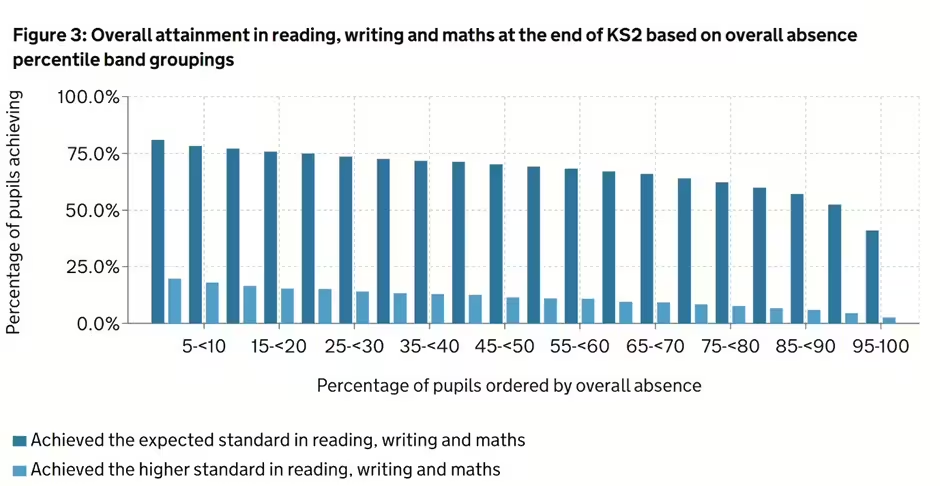

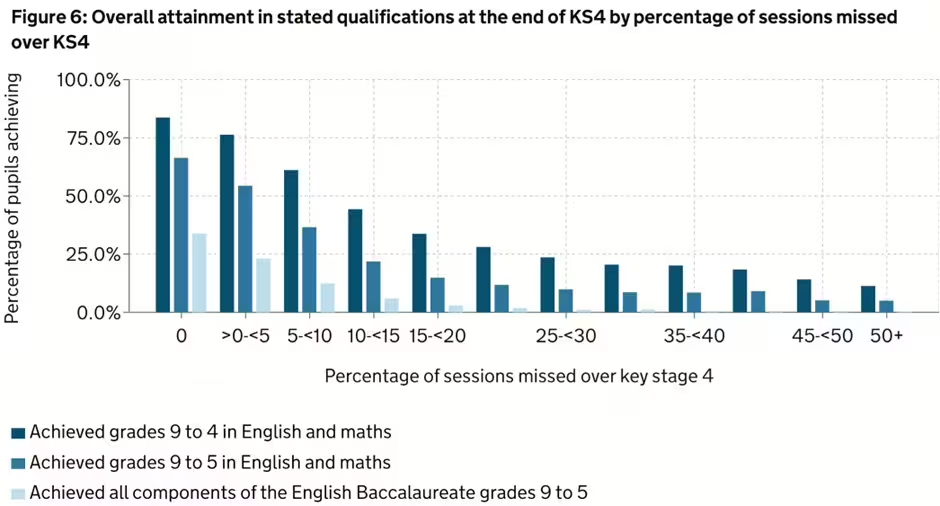

The Department for Education also collects and publishes data regularly to encourage schools to focus on issues regarding absence – daily sharing of attendance data is mandatory from August 2024. The education of the minority of students who miss large amounts of schooling is negatively impacted by their time away from learning; there is a clear link between absence and attainment and this link is consistent over time.

The Covid pandemic has had an impact on absence; there is clear evidence that more absence is due to illness than pre-pandemic. There also suggestions that some students and families are less inclined to view absence negatively than previously.

Absence is an issue across the world, with reports in the USA suggesting parents and students are “less conscientious about schooling and more conscientious about health”.

In summary, schools need to reduce unauthorised absence as much as possible, as they have done in the past to ensure that students are in school and in class.

What does the research say?

Most of the focus is on preventing future absence rather than action to address missed learning.

The Education Endowment Foundation has a section on Supporting school attendance:

- There is some evidence of promise for parental communication and engagement approaches and responsive interventions that meet the individual needs of pupils.

- The interventions that show promise take a holistic approach in understanding pupils and their specific needs and address the specific barriers to attendance that have been identified. For example, one programme found to have a positive impact on attendance used several different approaches depending on the needs of pupils, including a team to monitor and track attendance, parental communication, and motivation systems.

The EEF notes that much of the existing evidence is from the USA and from settings which are not particularly similar to England. Much of the evidence was undertaken pre-Covid. The majority of studies involve secondary school students rather than those in primary.

The EEF includes some useful guidance in its ‘Working with parents to Support children’s learning’ advice. This includes advice about creating open channels of communication with parents, which can be particularly useful for those families with students at risk of future higher-than-typical absence.

There is almost no research into successful strategies to address missed learning due to absence. This seems odd, given schools’ increasing ability to track absence with more precision over time.

Additionally, very few schools support teachers in their tracking of missed lessons due to absence, and missed learning is not routinely recorded within a school’s databases. Given that the majority of absence is due to illness – and national attendance patterns suggest students miss around 3% of learning time through illness – this in an area which may worth exploring in future.

Official Guidance

The Department for Education issued guidance for schools in 2022 (which has been updated for 2024) called Working together to improve school attendance. This has been updated to take account of new legislation which schools have to follow from August 2024.

The guidance has three pages with the following headings in a 67-page document:

This doesn’t say anything particularly useful about tackling issues related to attendance, other than making it clear that attending school and keeping accurate attendance and absence data is important. Whilst the document recommends analysing data, it does so to identify students and families who should be supported to avoid absence in future.

What do schools actually do to address attendance issues?

Ways to reduce future attendance issues may include:

- Using historic data to identify individuals and families with historically high absence.

- Proactively contacting families before the start of the school year/term to highlight previous low attendance and support available to support attendance.

- Introducing incentives for persistent absentees to maximise their attendance.

- Closely monitoring absences as they arise, with phone calls, text messages and face to face conversations to address any issues preventing school attendance.

- At population level, there are clear correlations between SEND and measures of deprivation, and schools should always be aware of wider contextual factors which may prevent regular school attendance.

- Many if not all primary schools celebrate attendance in assemblies and newsletters to raise awareness of the importance of attendance.

- Secondary schools are more likely to make it clear to their community that missing school is associated with lower GCSE grades.

In conclusion

Students need to be in school and in class. Most students have high attendance but a significant number do not. Any lessons missed will have an impact on a student’s education. Most schools track attendance and aim to reduce future absences.

There is an opportunity to make better use of data to understand patterns of absence, to help teachers to track lessons and learning missed and to make changes to allow pupils who miss learning opportunities in school to catch up key learning they may have missed.

Are you interested in exploring the current state of data in schools and finding out what works and what doesn’t? Join us at one of our 2024-25 Data in School Conferences

“I thought it was brilliant! I got home and did a SWOT analysis of assessment in our school to help focus where we are and where we need to go next. I just wish all the leaders in my Trust could’ve been there.” (attendee of DISCO Solihull, 23 Nov 2023)

Leave a Reply