Most students are in school most of the time, most absence is due to illness and family holidays during term time represent a small but consistent rate of overall absence.

Much of the discourse about attendance in English schools focuses on those students who are absent from school and what happens if families take children out of school during term time. Attendance has been subject to increasing government focus since 2017, when the Supreme Court ruled that ‘regular attendance at school’ meant children should be expected to attend school for every session. The current DfE guidance (first introduced in September 2022) is ‘Working together to improve school attendance’; it emphasises the importance of school attendance and the expectation of schools.

We look here at patterns of attendance and absence to shine light on what we know based on the evidence available.

Attendance data has been collected centrally by the state in a number of ways since 2006. Schools had to maintain registers which could be inspected by outside bodies, but there was no central collation of the data. Prior to 2006, national attendance patterns were monitored via an Absence in Schools Survey introduced in 1993.

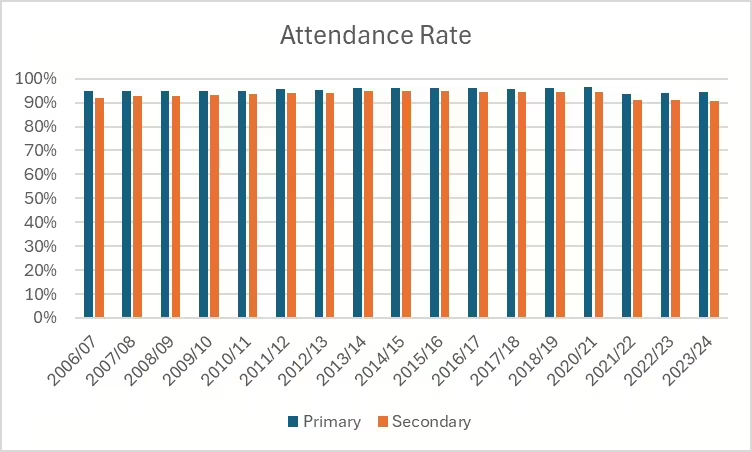

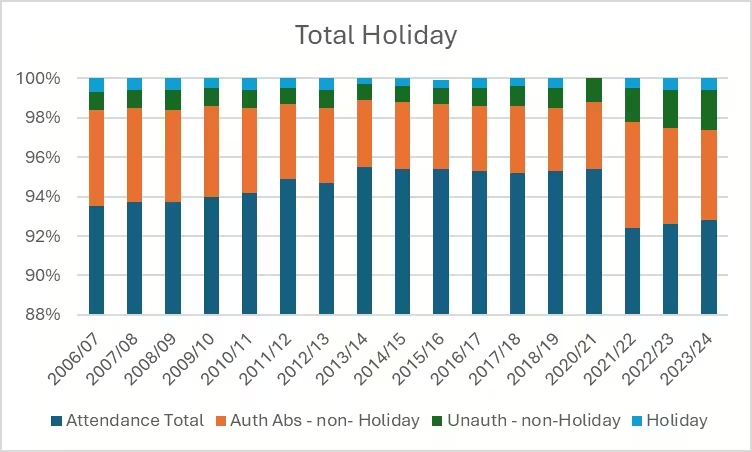

From 2006 until 2024, Inspectors and Local Authorities could ‘make extracts’ of registers, and schools had to make a return including details of those students who failed to attend regularly or had been absent without authorisation for more than ten school days. This enabled the DfE to collect termly returns allowing them to create the data which is in the chart below.

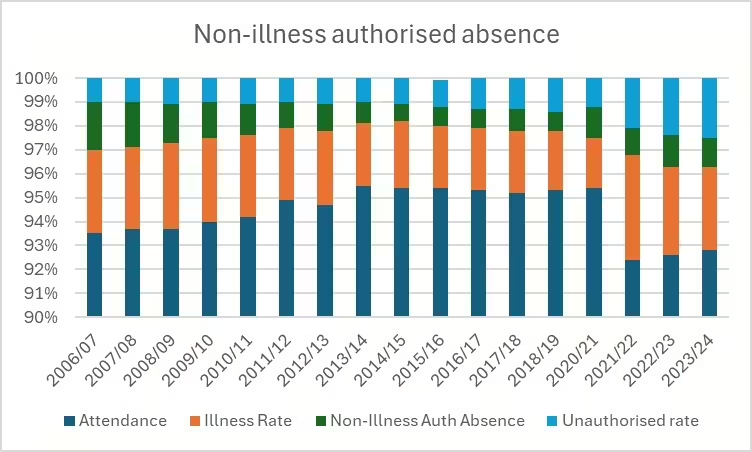

As is clear from this table, the vast majority of students are in school when they should be. Attendance has not fallen below 92% overall since 2006, with attendance in primary schools not falling below 94% in any year. Attendance in secondary has always been above 90%.

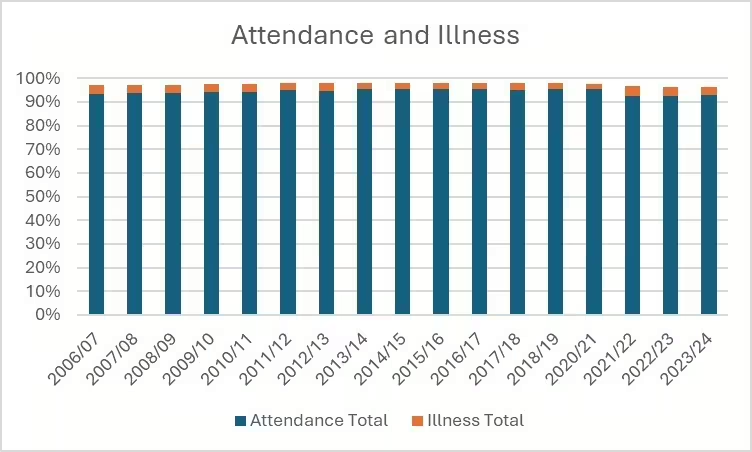

Since 1996, by law, schools have had to categorise those students who are not in school using a series of codes which have developed over the years. One of these codes records when a student has been registered as being ill. The majority of absence is due to illness, as per the chart below.

Students can be registered as being absent for reasons which are either classified as authorised or not authorised. Illness is recorded as authorised absence, as are several other categories including work experience, medical appointments, religious observance and so on.

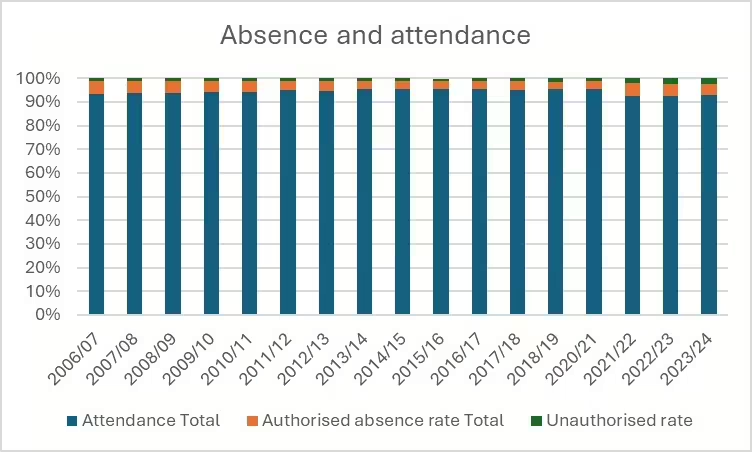

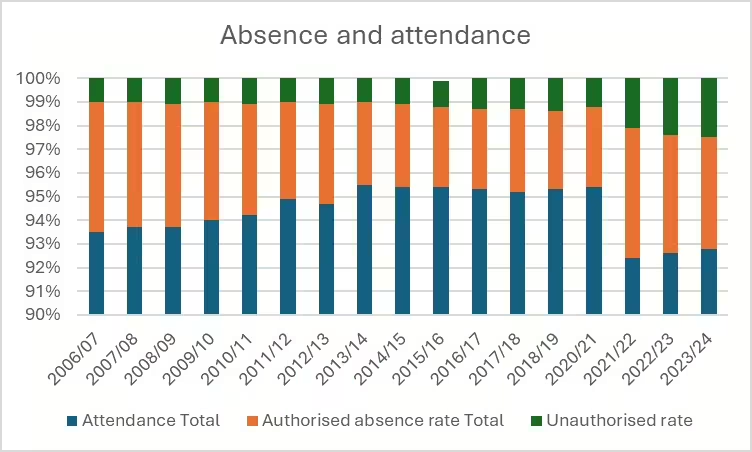

Attendance plus authorised absence has not fallen below 97.5% since 2006.

The school system had progressively reduced the rate of authorised absence between 2006/7 and 2020/21, partly as a result of the directive to classify non-illness absence as unauthorised absence and partly as a result of an increased focus on attendance as a driver of success at school.

As a result of the impact of the Covid pandemic, however, the rate of authorised absence increased substantially between 2020/21 and 2021/22, from 3.4% to 5.5% (a 60% increase). There is some suggestion that this might be because the rate of authorised absence due to illness has increased (students appear to be taking longer to return to school after periods of illness compared to pre-pandemic).

Authorised absence has been decreasing steadily since 2021/22 and is currently at the same level as it was in 2010/11.

The rate of unauthorised absence had increased from 1% in 2010/11 to 1.4% in 2018/19. This is likely to be due to schools classifying some absence as unauthorised where it may previously have been classified as authorised. Unauthorised absence improved slightly during 2020/21 (the year immediately after the initial Covid 19 outbreak) before deteriorating from 2.1% in 2021/22 to 2.5% in 2023/24.

By separating out illness from other authorised absence, we can look more clearly at the ‘non-illness authorised rate’ of absence. This reduced from 2006/7 to 2018/19 – from 2% to under 1% – and, after a slight rise in 2020/21 – has begun to reduce again.

One key talking point regarding attendance has been number of families taking holidays during term time. Demand for family holidays reduces dramatically outside of school holidays, which appears to have encouraged some families to take children out of school to take advantage of lower cost holidays offered during term time.

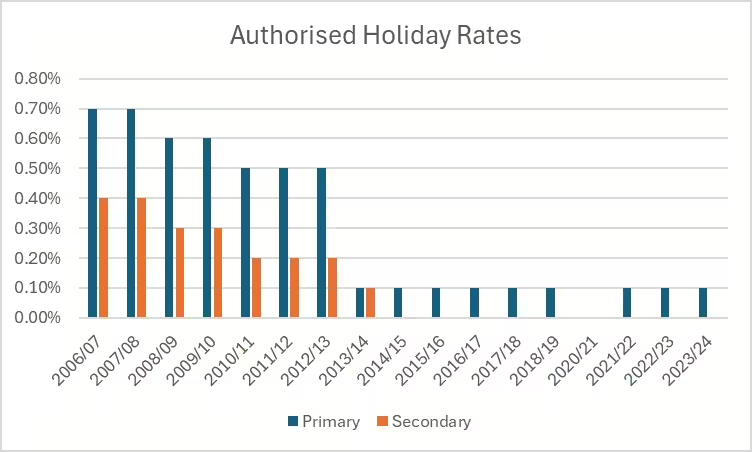

Additionally, legislation introduced in 2006 tacitly accepted that families were taking children out of school during term time, and attempted to limit these periods of absence to no more than ten school days in any school year. In 2007, fines for absence of £50 per parent per child, at a school’s discretion, were introduced. In 2013, the DfE amended the legislation to clarify that ‘leave of absence shall not be granted by schools unless there are “exceptional circumstances”’, claiming that ‘parents and some schools have interpreted this law as an automatic entitlement to an annual two-week term time holiday’. Additionally, fines were increased to £60.

In effect, the change in 2013 meant that schools could not authorise leave of absence for family holidays during term time.

These changes are reflected in the graph below. Secondary schools unanimously stopped authorising family holiday absence from 2013. Primary schools stopped authorising the majority of requests for family holiday absence.

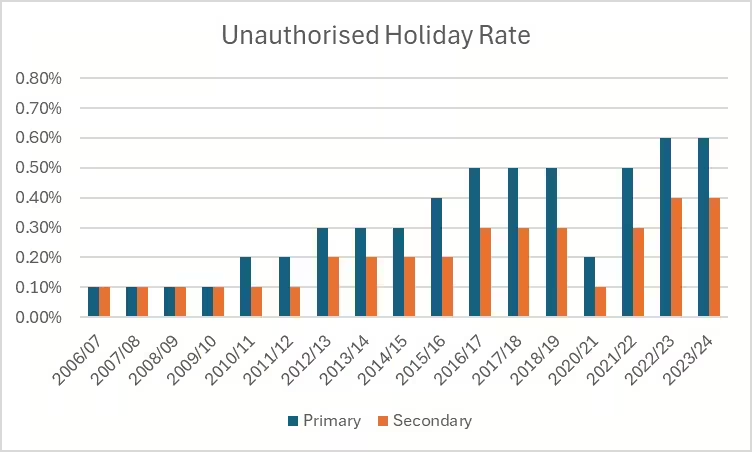

The impact of these changes on unauthorised holiday rates are shown below.

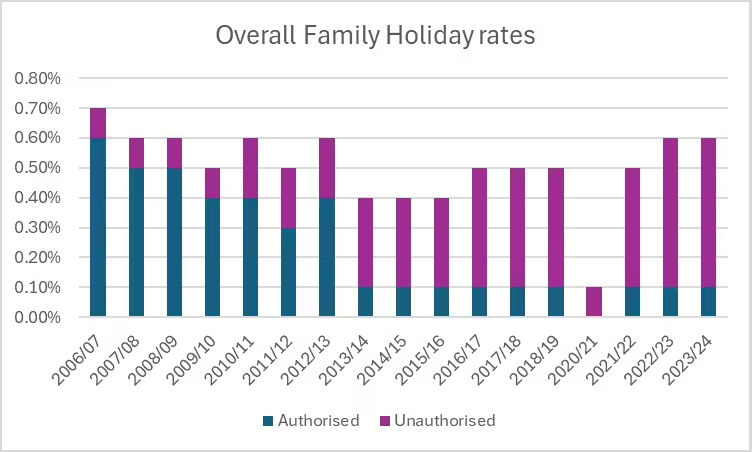

Looking at both authorised and unauthorised holiday absences, an interesting picture emerges. It seems that the rate at which families take children out of school during term time has not altered a great deal since 2006/7. Whilst the change in legislation made a small difference to the overall holiday rates in 2013 to 2016, current rates are broadly similar to those of 2007 to 2013. A small but notable number of families continue to take holidays in term time. The difference between now and the 2000s is that this holiday is now unauthorised and parents are fined for term time holidays.

When seen in the context of other authorised and unauthorised absence, holiday rates count for a consistently small proportion of overall absence.

Whilst every day out of school represents a day’s lost learning, we should recognise that most students are in school most of the time, most absence is due to illness and family holidays during term time represent a small but consistent rate of overall absence.

(This piece is included as part of the Insight Inform launch report published on 7th September. We have also released our first Insight Inform podcast introducing Insight Inform, the new information service from Insight).

Leave a Reply