Levels were fine until they weren’t.

Used until 2015, they provided a broad indicator of attainment at the end of each key stage and gave a notion of progress as children moved from one level to the next. The rot set in when they began to be used for accountability purposes, especially measures of progress, which decreed that pupils from all starting points needed to make a set number of levels over a set period. Before long, schools were faced with an expectation that all pupils would make at least two levels across key stage 2, and three levels between key stage 2 and 4. And there was an unwritten rule that at least a third would go beyond that ‘expected’ rate.

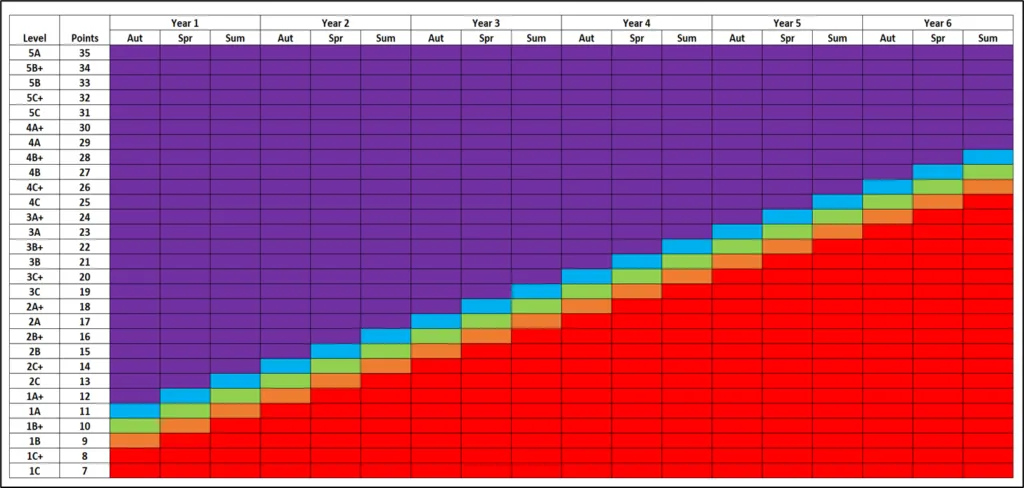

Then, as schools came under increasing pressure to show progress over ever shorter periods, levels became subdivided, first into a series of sub-levels, and then into sub-sub-levels, or points. By 2014, when the government of the day made the decision to ditch the levels system from the national curriculum, teachers were convincing themselves that they could differentiate between a 3b and a 3b+. Or, at least, pretending they could.

Inevitably, when levels went, schools, LAs, assessment providers, and developers of tracking systems set about recreating them; and in many ways what came next was worse than the levels they replaced. Initially, sub-levels were renamed but, before long, the old ‘point per term’ orthodoxy mutated into a point per half-term or even a point per month, as if inventing more bands proved that pupils made more progress. The final report of the Commission on Assessment without Levels warned us that ‘tracking software, which has been used widely as a tool for measuring progress with levels, cannot, and should not, be adapted to assess understanding of a curriculum that recognises depth and breadth of understanding as of equal value to linear progression’. Sadly, that advice was lost in the clamour for new metrics.

Early Years, meanwhile, was largely excluded from conversations about assessment without levels, which may seem like an obvious thing to say considering levels did not apply to pre-key stage 1 education. But levels were in use in Early Years; they just weren’t called levels. The age and stage bands of the Development Matters framework were commonly used as a tool for measuring progress, and this, again, was encouraged by LAs and adopted wholesale by providers of tracking systems. This is despite the framework stating that ‘Children develop at their own rates, and in their own ways. The development statements should not be taken as necessary steps for individual children. They should not be used as checklists. The age/stage bands overlap because these are not fixed age boundaries but suggest a typical range of development.’

All of this was ignored in the pursuit of a progress measure. The inconvenient overlap between the age/stage bands was overlooked; instead, the bands were deemed to be discrete and hierarchical. Inevitably, the age/stage bands were then broken down into three or more sub-levels – usually named emerging, developing, and secure – and each sub-level was pinned to a specific point in time. This allowed the system to colour code children according to whether they were below, at, or above age-related expectations and show if their progress was below, in line with, or above the expected rate. Schools’ systems were therefore out of kilter with what teachers know about child development: that ‘Children develop at their own rates, and in their own ways’ and that children at different stages of development can be deemed ‘typical’ when their relative ages are taken into account.

And now we come to SEND. After a somewhat protracted process, extended by the pandemic, P scales were finally removed from national assessment frameworks in 2022 and have been replaced by the engagement model and a series of pre-key stage standards. The Rochford Review report of 2016 gave a number of reasons for this decision, which centred on concerns that the existing system of p-scales reinforced a ‘linear progression’ mindset; that ‘there is a built-in incentive for schools to encourage progression on the next P level before pupils have acquired or consolidated all elements of the previous P level’; and that there was a need to ‘recognise lateral progress.’ The reasons given for the removal of P scales were remarkably similar to those given for the removal of levels.

Schools have largely weaned themselves off linear progression models and flight paths for the mainstream, but SEND is proving a sticking point. A need to measure the ‘small steps’ of progress is a common reason given, and all manner of approaches have been developed to that end. Unsurprisingly, considering one numerical scale was replaced by another, the new system of pre-key stage standards have been commandeered for the task, and in some cases broken down into sub-levels to provide the desired smaller steps. And old levels-style systems – with their built-in assumption that pupils should make a curriculum year’s worth of progress per year – have been brought down from the attic, dusted off, and pushed back into service.

Levels, age/stage bands, p-scales – all of them yielded to the strain of accountability. With the bands getting divided into an ever-increasing number of subunits to supposedly show more and more progress over shorter and shorter periods, teachers resorted to adding a point at each data drop to keep everyone happy. The pressure to measure progress had broken the building blocks of assessment. If you bend something beyond its elastic limit, it snaps.

What can we learn from this?

If a progress measure is the hub on which your assessment system is built, then the wheel almost certainly isn’t going to run true. Learning will be reduced to a constant gradient, teachers will be tempted to add the required number of points each term, and the data will soon be out of kilter with reality. Instead, collect data that indicates whether pupils are working below, within or above expectations and report the percentages to governors. This will provide them with more insight into standards across the school than abstract numerical proxies of progress. You don’t need a great deal more data on pupils that are meeting expectations; instead focus on collecting useful information about those that require additional support.

For an assessment system to be effective it needs to be a) free from distorting effects, and b) honest. Progress measures – especially those based on teacher assessment – are a problem on both counts: they result in the distortion of data because they’re not real.

In short, progress measures break assessment.

Are you interested in exploring the current state of data in schools and finding out what works and what doesn’t? Join us at one of our 2024-25 Data in School Conferences

“I thought it was brilliant! I got home and did a SWOT analysis of assessment in our school to help focus where we are and where we need to go next. I just wish all the leaders in my Trust could’ve been there.” (attendee of DISCO Solihull, 23 Nov 2023)

Leave a Reply