Many years ago, following a meeting of the Reception Baseline Stakeholder Group at DfE Towers, I went for a cup of tea with a fellow group member and was told a story that blew my mind. As we sat sipping English breakfast in the well-lit atrium, my partner-in-tea asked, “do you know how the expected standard is set?” and proceeded to explain the concept of ‘bookmarking’.

When setting a pass mark for a test, you have various options. You could just pick an arbitrary threshold and require pupils to achieve a certain percentage of the marks. The problem here is obvious: what happens when the test varies in difficulty? Can we then compare a pass from one year to the next? Given that the phonics screening check’s pass mark has been fixed at 32/40 (80%) since its inception, one wonders if a number was selected and maintained simply for the sake of convenience.

Another option is norm referencing. Here, we are effectively ranking all pupils on the basis of their scores, and then selecting a certain percentage as having passed the test – the top 60% for example. This is more resistant to changes in test difficulty – the raw score associated with the required rank position will fluctuate – but it is not without issues. First, we will end up with the same percentage passing each year, which won’t show the improvements in standards that a government inevitably wants to show. And second, we still can’t reliably compare a pass from one year to the next – a pupil might make the cut one year because of a dip in the ability of the national cohort.

And then we have criterion referencing. This involves establishing a set of criteria that pupils need to meet if they are to pass the assessment. A driving test is a good example of this: if you meet the criteria, you pass the test. The assessment of writing at Key stage 2 is another example: teachers collate evidence to demonstrate that pupils have met each of the descriptors listed in the assessment frameworks. And the expected standard based on a key stage 2 test is also a form of criterion-based assessment, but the way in which it is set is somewhat more complex and arcane.

Two groups of experts – in this case, teachers with excellent knowledge of the national curriculum and assessment – are brought together to assess the results of national reference tests. They are presented with a list of test items (questions) ranked in ascending order of difficulty based on the percentage of pupils that answered each correctly. Working individually, group members then place a bookmark at the point where they believe pupils have reached the expected standard. Once this stage is completed, teachers discuss the results in small groups, the aim being to iron out any big differences in opinion. At this point, impact data may be shown, which reveals the percentage of pupils that would meet the expected standard if the threshold is set at the proposed point. The group can then re-evaluate their decision in the light of this information. And finally, the respective bookmarks are collated and debated as a group and a consensus arrived at. The same process is undertaken by the other group, working in a different room, and the testing agency is presented with two results, from which they pick one. This becomes the expected standard, which at key stage 2 equates to a score of 100. Work is then carried out each year to maintain the expected standard at a comparable level, which means that the pass mark fluctuates to reflect changes in difficulty. In theory, we have a consistent measure of competency.

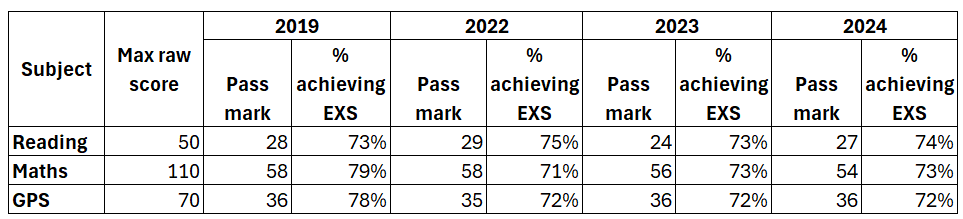

Therefore, unlike the phonics test – where the pass mark remains the same but the percentage passing it changes – and a norm-referenced threshold – where the raw pass mark may change but the percentage that passes remains constant – in key stage 2 tests, both the raw pass mark and the percentage achieving the expected standard change over time. This is demonstrated by the following table:

Increases in the pass mark suggest a more difficult test that year; where the pass mark drops, the test is deemed to be a bit easier. Changes in the percentage of pupils achieving expected standards from one year to the next should therefore reflect shifts in national standards, which is what the government is most interested in monitoring.

It is worth noting that the first group to attempt these new tests – and whose results informed the expected standard – was the 2016 year 6 cohort. These pupils had had just two years experience of the new national curriculum since it was introduced in 2014. At the time, the government proposed a floor standard that required 85% to meet the new expected standard in reading, writing and maths, but this was quietly dropped back to the 65% threshold schools had been held to under levels, possibly due to the realisation that very few schools would meet it. In the event, 66% of pupils met the expected standard in reading that year, and just 53% met the standard in the three subjects combined. England had fallen 12 points below its own floor.

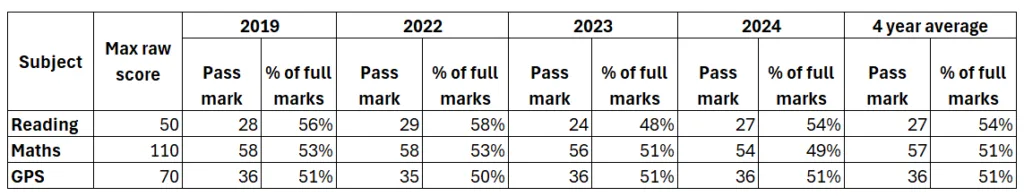

But enough of the history detour, let’s return to the above table and dig a bit deeper into what it means to meet the expected standard. The following table shows the pass mark alongside the percentage of total marks required to reach the threshold. On average, a pass requires just over half of the marks and in two cases – reading in 2023 and maths in 2024 – just under half.

It is not the intention of this post to question the rigour of the standards setting process. And meeting the standard is clearly challenging for many children – certainly more challenging than securing the old level 4. Rather, it is how the unavoidable focus on meeting expected standards plays out in terms of tracking pupil progress and the impact this may have on learning. Just about all primary schools administer ‘practice SATS’ at some point during year 6 and many schools will run these tests multiple times, perhaps every half-term or even more frequently. The main purpose of this exercise is to prepare pupils for tests and check if they are on-track to achieve expected standards in May. And, much like with GCSEs, there may be greater focus on ‘borderline’ pupils, with increased efforts made to boost their scores, to get them over the magic line. By concentrating on these thresholds, we are essentially sifting cohorts into two groups: those that are likely to secure more than half of the marks in the tests, and those that are at risk of falling short. It becomes more about numbers than knowledge.

So, what’s the alternative?

As long as we have key stage 2 tests, schools are going to want pupils to practise them – that’s not going to change – but the DfE could consider not publishing the mark schemes and conversion tables. Pupils would still be able to attempt past papers, but schools wouldn’t be able to convert results into scaled scores. An even more radical (and controversial!) solution is to stop publishing the past papers entirely and instead make questions available via an online question bank, from which schools can construct their own tests. Such systems already exist and are commonly used by schools. Both of these options could help shift the focus away from a threshold that requires pupils to get just over 50% of the marks on a test.

The most radical solution of all, of course, would be to cease universal testing at key stage 2 and move to a system of sampling. This was previously done for science in England and is a common approach taken in other countries. In France, for example, CEDRE assessments are undertaken by several thousand randomly selected 10- and 11-year-old pupils each year. The results are used to monitor national standards but cannot be used to evaluate the performance of individual schools.

Primary schools operate in a system that builds towards tests that require pupils to secure just over half the marks; and a pupil that does this is deemed to have passed. Because of the high stakes nature of these tests, a great deal of effort is expended in attempting to predict results. But do we risk sacrificing deeper and broader learning at the altar of these of expected standards? Is ‘expected’ enough?

It will take some bold decisions to change this culture.

Leave a Reply