“Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could, they didn’t stop to think if they should.” (Dr Ian Malcolm, Jurassic Park)

Say what you like about Progress 8, at least it involves a standardised test at each end (hint: progress measures should always involve a standardised test at each end!). The problem with measures of progress in primary settings is that they inevitably involve an element of teacher assessment somewhere. Having progress measured from a baseline – e.g. key stage 1 assessment – that schools themselves have control over seems normal, but it’s actually fairly weird when you think about it. In an infant school, key stage 1 assessment is purely a result; in a junior school, it’s a baseline. But, in an all-through primary school, it plays both roles, and this places the assessment in tension. Under such circumstances, the gravitational pull of the baseline is hard to resist, and schools are likely to err on the side of caution. So, we end up with the assessment at one end yielding to the stress of accountability and bending beyond its elastic limit. And just so we’re clear here, this is not an issue specific to schools. As Daisy Christodoulou says, “Teacher assessment is biased not because it is carried out by teachers, but because it is carried out by humans.”

But at least the assessment at the key stage 2 end is based on a standardised test, right?

Yeah. We need to talk about writing.

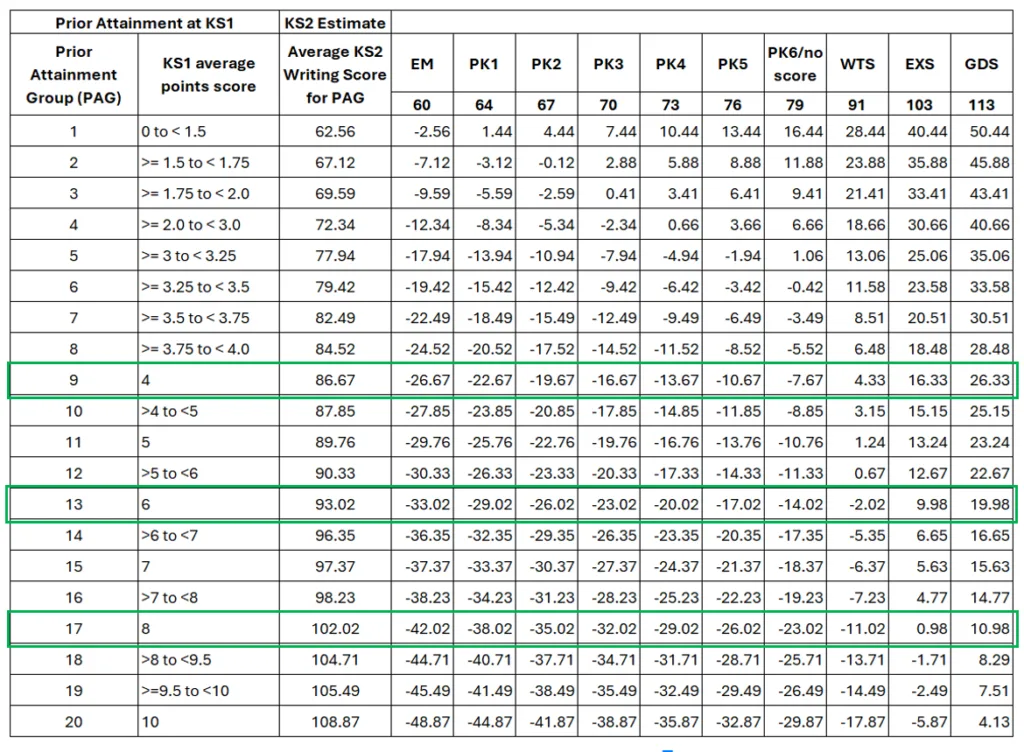

The table above shows every possible progress score for each of the key stage 1 prior attainment groups (PAGs) and outcomes at key stage 2. Column 2 is the key stage 1 average point score, which defines the prior attainment groups, and column 3 contains the benchmark score that pupils in a particular prior attainment group need to exceed to gain a positive progress score. Normally – in the case of reading and maths – the benchmark is the national average test score of the pupils in the prior attainment group. And because most pupils sit tests and achieve an actual score, they can get close to the benchmark. This is not the case for writing, however, where no test exists. Instead, they are awarded a teacher assessment which in turn is assigned a ‘nominal score’ – a sort of quasi-test score – as shown in the following table.

| Assessment | Nominal Score | Assessment | Nominal Score |

| EM | 60 | PK6 | 79 |

| PK1 | 64 | N* | 79 |

| PK2 | 67 | Writing Only | |

| PK3 | 70 | WTS | 91 |

| PK4 | 73 | EXS | 103 |

| PK5 | 76 | GDS | 113 |

The benchmark is, therefore, the average of the nominal scores of the pupils in a prior attainment group, and a pupil’s nominal score is compared to the relevant benchmark to generate their individual progress score. The problems here are twofold: 1) there are big leaps in score between the bands, especially the main ones (WTS, EXS, GDS), and 2) it’s based on teacher assessment.

Let’s return to the original table and discuss some of the issues this creates. First, look at prior attainment group 9, with a key stage 1 average score of 4, which represents a pupil that was at pre-key stage standard 4 at key stage 1. If they remain pre-key stage at key stage 2, they will end up with a progress score of -7.67 at best, which could inflict a notable dent in the school’s overall progress score. To achieve a positive progress score, they would need to be assessed as ‘working towards the expected standard’ (WTS) at key stage 2, which – because of the 12 point leap in score between bands – would push their progress score to +4.33.

Now look at prior attainment group 13, which represents a pupil that was, on average, WTS at key stage 1. Their key stage 2 benchmark is 93.02, which suggests that maintaining WTS at key stage 2 would be sufficient in terms of progress. Unfortunately, WTS in writing at key stage 2 attracts a nominal score of 91, which would result in a pupil progress score of -2.02. If, however, the pupil is assessed as working at the expected standard (EXS) in writing at key stage 2 – attracting a nominal score of 103 – their progress score shoots up to +9.98. Such a swing for one pupil could have a big impact on the school’s overall score.

And finally, consider prior attainment group 17, which represents a pupil that was working at the expected standard (EXS) across all subjects at key stage 1. The benchmark for this group is 102.02. Because of the nominal scores assigned to the various assessment bands, falling short of expected standards in writing – i.e. a WTS assessment – at key stage 2 would result in a progress score of -11.02, whilst meeting the expected standard (EXS) would just tip it into positive territory with a score of +0.98. Achieving greater depth (GDS) on the other hand would secure a progress score of +10.98. Considering the vagaries of moderation, differing interpretations of guidance, and the varying levels of stress that schools are under, this is far from an ideal system.

Now let’s consider the effect on the aggregate. First, sum the cohort’s individual progress scores – the difference between each pupil’s nominal score and the benchmark score for their prior attainment group – and then calculate the mean (omitting any pupils with missing or invalid results). For a one form entry school – a cohort of 30 pupils – having just one pupil assessed as working at the expected standard (EXS) in writing at key stage 2 rather than working towards (WTS) would increase the school’s overall progress score by 0.4. This is because the pupil secures a nominal score of 103 rather than 91 – a difference of 12 points – and 12 points divide by 30 pupils is 0.4. Now imagine a sliding doors’ moment: a school assesses the pupil as working towards in writing at key stage 2 and ends up with an overall progress score that is deemed ‘below average’. No one is happy: the governors are asking difficult questions; the parents’ perception of the school, gleaned from the performance tables, takes a hit; and Ofsted is looming. But the upper limit of the confidence interval, which defines the school’s performance band, is within 0.4 points of zero. In the parallel universe, the pupil achieves the expected standard, the overall progress score shifts up by 0.4, the school is no longer classified as ‘below average’, and the perception of the school changes for the better. Just one pupil moving up a band can do this – the big shifts in nominal score can cause big shifts in performance measures, which can lead to the distortion of data that is already prone to bias. The system is bending the very data it relies upon to function. As Goodhart’s Law states, “any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.” To put it another way: you can have accurate teacher assessment, or you can use it for accountability.

It is little wonder that some academies may exercise their freedoms by ‘shopping around‘ for more favourable moderation arrangements. It is also no surprise that the DfE do not to include key stage 2 writing results in the baseline for Progress 8.

And remember, this hasn’t gone away. After a two-year hiatus caused by missing key stage 1 results, the measure is scheduled to return in 2026.

Hopefully, by then, it will have gone the way of the dinosaurs.

Leave a Reply