In 2016, Becky Allen wrote an excellent article for FFT Education DataLab, which looked at how teacher assessments of writing compared to the results of the reading test at key stage 2. The data showed that there was little consistency within and between local authorities, and concluded that this variability most likely resulted from differences in moderation. The article identified local authorities whose moderation of writing may have been too harsh alongside those that were possibly more lenient. It’s worth pointing out that academies can choose which LA moderates their assessments, and there is some evidence to suggest that schools have been ‘shopping around’ for more more lenient moderation arrangements. LA maintained schools, meanwhile, have no such choice.

Suspicions about the reliability of KS2 writing assessment are nothing new, and it’s no surprise that the DfE decided to remove writing outcomes from the progress 8 baseline once they ran out of KS2 writing test scores in 2018*. This suspicion was reflected in Ofsted’s inspection data summary report (IDSR), which at one point flagged those schools whose results in writing were ‘considerably lower’ or ‘considerably higher’ than those in the other (i.e. tested) subjects. Schools in the former camp were less concerned, and perhaps even saw it as a badge of honour – proof of their robust assessment practices. Those in the latter camp, on the other hand, may have been more anxious, especially if an inspection was looming.

But what’s the current situation? 8 years on from that DataLab blog, how have things changed? To borrow a football cliché, it’s a game of two halves. Two halves separated by a pandemic.

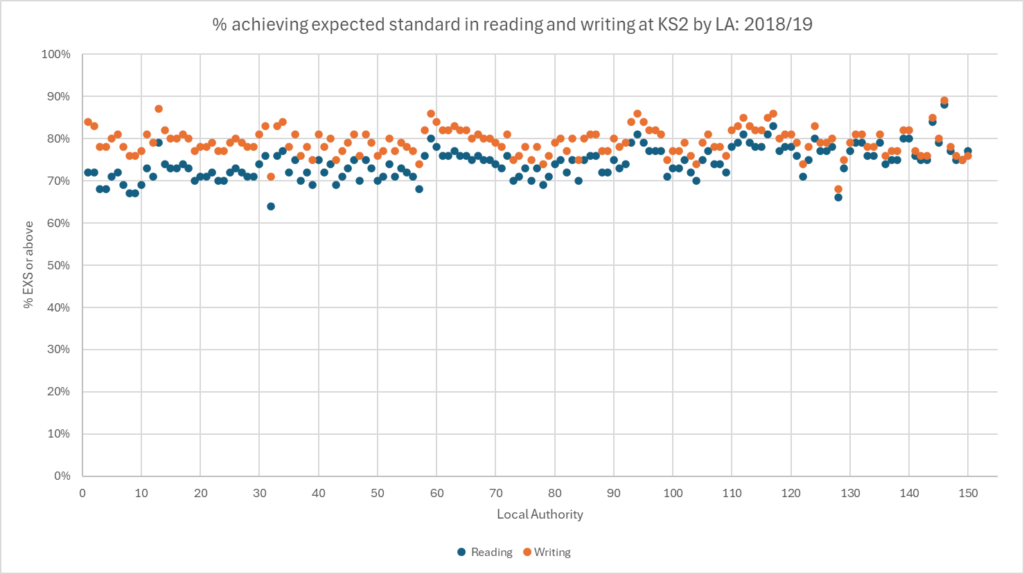

The following graph plots the percentage of pupils achieving expected standards in reading (blue dots) and writing (orange dots) at key stage 2 in 2019 for each local authority in England. Again, for clarity, writing results are based on teacher assessment; reading results are based on a test. In all but two local authorities, writing results were higher than reading (Knowsley’s results were equal; Windsor and Maidenhead’s reading result was 1pp higher than writing).

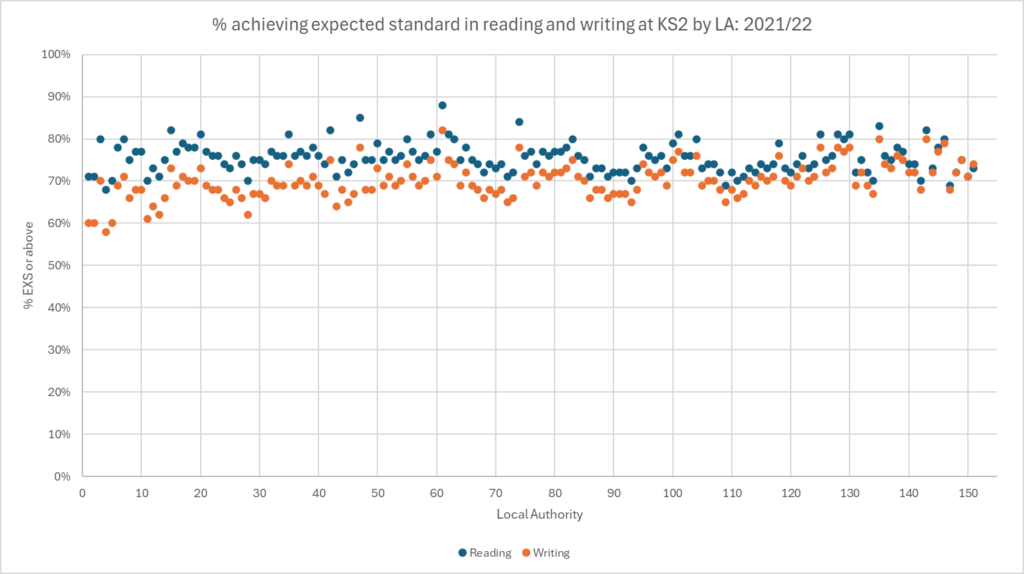

There are no results for 2020 and 2021 due to the pandemic. The next set of data is, therefore, for 2022.

Here we see a near complete reversal with reading results higher than writing in nearly all cases. Only North East Lincolnshire has a writing result that is higher than reading (by just 1pp), whilst North Lincolnshire, Thurrock, and Medway have reading and writing results that are on a par.

In 2019, the LAs with the biggest result gaps (writing > reading) are: Hackney, North Lincolnshire, Doncaster, Rotherham, Bolton, North East Lincolnshire, Coventry, Dudley, Portsmouth, Lincolnshire, Haringey, Swindon, Redbridge, South Gloucestershire

in 2022, the LAs with the biggest result gaps (reading > writing) are: Manchester, Oldham, Merton, Isle of Wight, Portsmouth, Hertfordshire, Windsor and Maidenhead, Knowsley, Sefton, Luton, Norfolk, Reading, Southampton, West Sussex, Wokingham

It’s interesting to see Portsmouth on both lists and further analysis reveals that Portsmouth LA saw the joint biggest drop in writing results (by 16pp) along with Oldham, the Isle of Wight, and Southampton (something happened on the south coast!).

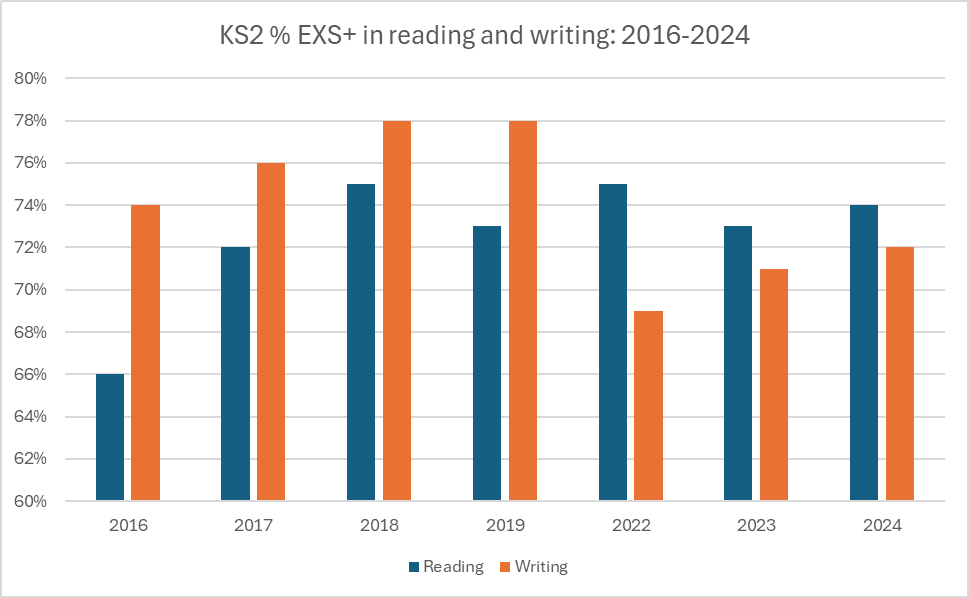

Between 2019 and 2022, there was barely any change in the reading results – surprisingly, the national figure actually went up from 73% in 2019 to 75% 2022 – but writing results fell dramatically across the country. The national figure fell from 78% to 69%, and over a third of local authorities saw a double-digit fall in their writing results compared with pre-pandemic levels.

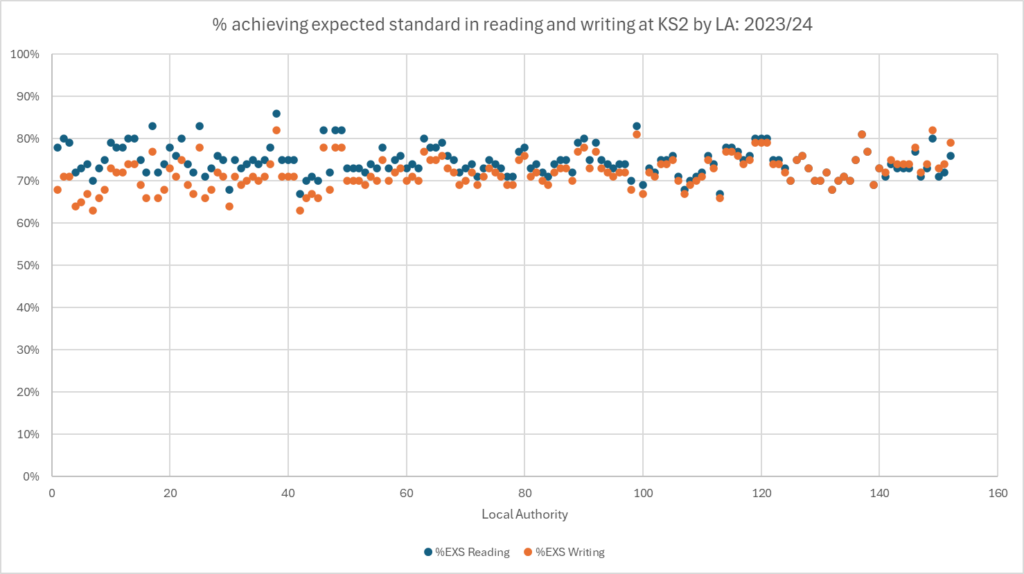

Between 2016 – when the first round of new national curriculum assessments took place – and 2019 – the last year of assessment before the pandemic – KS2 writing results were above reading every year. Since the pandemic the picture has flipped, and despite the gap narrowing, reading results are still above those in writing. In 2024, 80% of LAs had reading results that were higher than writing (shout out to Windsor and Maidenhead again who had the biggest gap of 10pp) and only twelve LAs had writing results that were higher than reading (the biggest gap – Thurrock – was just 3pp). This is a huge change from 2019 when it was all but two LAs.

Clearly, lockdowns had a huge impact on children’s education, and writing – difficult for parents to teach effectively at home – probably did suffer more than other subjects. But we also have to consider the possibility that the results since the pandemic represent a correction. There will always be inconsistencies with moderation, and using teacher assessment in high stakes accountability measures is highly problematic, but maybe writing results are now where they should have been all along.

And when we have more reliable data, we can start to make better decisions.

* the 2017/18 GCSE cohort were the first to have teacher assessments of writing at KS2 (in 2012/13) and their Progress 8 baseline was based solely on reading and maths test scores. The 2016/17 GCSE cohort had KS2 test scores in reading, writing and maths; and all were used for the Progress 8 baseline. At least I think that’s correct. Please let me know if you remember differently.

Leave a Reply